Why use an Entity Component System architecture for game development?

Following my previous post on entity systems for game development I received a number of good questions from developers. I answered many of them directly to the questioners but one question stands out. It's all very well explaining what an entity component system framework is, and even building one, but why would you want to use one? In particular, why use the later component/system architecture I described and that I implement in Ash rather than the earlier object-oriented entity architecture as used, for example, in PushButton Engine.

So, in this post I will look more at what the final architecture is, what it gives us that other architectures don't, and why I personally prefer this architecture.

The core of the architecture

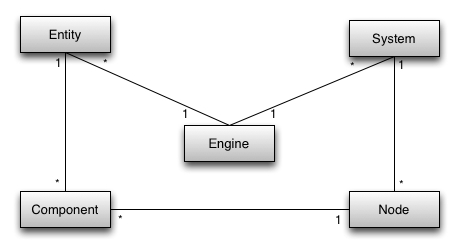

First, it's worth noting that the core of this architecture is the components and the systems. Components are value-objects that contain the state of the game, and systems are the logic that operates on that state, changing it as the game progresses. The other elements of the architecture are purely incidental, designed to make life easier.

The entity object is present to collect related components together. The relation between components is encapsulated by the concept of an entity and that is vital to the architecture, but it isn't necessary to use an explicit Entity object for this. There are some frameworks that simply use an id to represent the entity, adding the entity id to every component to indicate which entity it belongs to.

As a concept, the entity is vital to the architecture. But as a code construct it is entirely optional. I include it because, when using an object-oriented language, the entity object makes life easier. In particular, it enables us to create the methods that operate on the entity as methods of an entity object and to track and manage the entity through this object, removing the need to track ids throughout the code.

While the concept of an entity is vital to the architecture, the concept of node objects is entirely incidental. The nodes are used as the objects in the collections of components supplied to the systems. We could instead provide each system with a collection of the relevant entities and let the systems pull the components they want to operate on out of the entities, using the get() method of the entity.

In Ash, the nodes serve two purposes. First they enable us to use a more efficient data structure in which the node objects that the systems receive are nodes in a linked list. This improves the execution speed of the framework.

Second, using the node objects enables us to apply strong, static typing throughout our code. The method to fetch a component from an entity necessarily returns an untyped object, which must then be cast to the correct component type for use in the game code. The properties on the node are already statically typed to the components' data types, so no casting is necessary.

So, fundamentally, the entity architecture is about components and systems.

This is not object-oriented programming

We can build our entity architecture using an object-oriented language but, on a fundamental level, this is not object-oriented programming. The architecture is not about objects, it's about data (components) and sub-routines that operate on that data (systems).

For many object-oriented programmers this is the hardest part of working with an entity system framework. Our tendency is to fall back to what we know and as an object-oriented programmer using an object-oriented language that means encapsulating data and operations together into objects. If you do this with a framework like Ash you will fail.

Data-Oriented Programming

Games tend to be about lots of fast changing state, with players, non-player characters, game objects like bullets and lasers, bats and balls, tables and chairs, and levels, scores, lives and more all having state that might include position, rotation, speed, acceleration, weight, colour, intention, goals, desires, friendships, enemies and more.

The state of the game can be encapsulated in this large mass of constantly changing data, and on a technical level the game is entirely about what this data is and how this data changes.

In a game a single little piece of this data may have many operations acting on it. Take, for example, a player character that has a position property that represents the character's position in the game world. This single piece of data may be used by

- The render system, to draw the player in the world.

- The camera system, to position the camera relative to the player.

- The AI systems of all non-player characters, to decide how they should react to the player.

- The input system, which alters the player's position based on user input.

- The physics system, which alters the player's position based on the physics of the game world.

- The collision system, which tests whether the player is colliding with other objects and resolves those collisions.

and probably many more systems besides. If we try to build our game using objects that encapsulate data with the operations that act on that data, then we will build dependencies between all these different systems as they all want to be encapsulated with the player's position data. This can't be done unless we code the game as one single, massive class, so inevitably we break some parts of the game into separate systems and provide data to those systems - the physics system, the graphics system - while including other elements of the game logic within the game objects themselves.

An entity architecture based on components and systems takes the idea of discrete systems to its logical conclusion. All operations are programmed as independent systems, and all game state is stored separately in a set of data components, which are provided to the systems according to their need.

The systems are decoupled from each other. Each system knows only about itself and the data it operates on. It knows and cares nothing at all about the other systems and how they be affected by or use the data before or after this system gets to work with it.

Also, by embracing the system as the core logic of the architecture, we are encouraged to make many smaller and simpler systems rather than a few large complex ones, which again leads to simpler code and looser coupling.

This decoupling makes building your game much easier. It is why I enjoy working with this form of entity system so much, and why I built Ash.

Storing the game state

Another benefit of the component/system architecture is apparent when you want to save and restore the game state. Because the game state is contained entirely in the components, and because these are simple value objects, saving the game state is a relatively simple matter of serialising out the components, and restoring the game state involves just deserialising the data back in again.

In most cases, serialising a value-object is straightforward, and one could simply json-encode each component, with additional data to indicate its entity owner (an id) and its component type (a string), to save the game state.

Adam Martin wrote about comparing components in an entity system framework to data in a relational database (there's lots of interesting entity related stuff on Adam's blog), and emphasising that conversion between a relational database for long-term storage and components for game play doesn't require any object/relational mapping, because components are simple copies of the relational database's data structure rather than complex objects.

This leads further to the conclusion that a component/system architecture is ideal for an MMO game, since state will be stored in a relational database on the game servers, and much of the processing of that state will occur on the servers, where using a set of discrete, independent systems to process the data as the game unfolds is an excellent fit to both the data storage requirements of the state and the parallelism available on the servers.

Concurrency

Indeed, a component/system architecture is well suited to applying concurrency to a game. In most games, some of the systems are entirely independent of each other, including being independent of the order in which they are applied. This makes it easy to run these systems in parallel.

Further, most systems consist of a loop in which all nodes are processed sequentially. In many cases, the loop can be parallelised since the nodes can be updated independently of each other.

This gives us two places in the code where concurrency can be applied without altering the core logic of the game, which is inside the loop in the systems, or the core state of the game, which is in the components.

This makes adding concurrency to the game relatively simple.

We don't need object-orientation

Finally, because the component/system architecture is not object-oriented, it lends itself to other programming languages that implement different programming paradigms like functional programming and procedural programming. While I created Ash as an Actionscript framework, this architecture would be well suited to Javascript for client side development or any of the many functional languages used for highly concurrent server side development.

Update: In-game editors

Tom Davies has pointed out that a very valuable benefit to him is how easy it is to create an in-game level editor when developing with an entity system framework like Ember or Ash. You can see his example here.

The complete separation of the game state and the game logic in an entity system framework makes it easy to create an editor that lets you alter the state (configuration, level design, AI, etc.) while playing the game. Add to this the easier saving and loading of state and you have a framework that is very well suited to in-game editing.

Also in the collection Entity-Component-System architecture